One of our fish tank cleaners at the Information Aquarium recently slid this pamphlet from 1966 under the door of our lead slime mold scientist after their graveyard shift. Apparently, they found the booklet in a plastic sleeve wedged between the aquarium wall and one of the pumps.

Louella E. Cable wrote and produced Fishery Leaflet 583 in July 1966 for the United States Government’s elite Bureau of Commercial Fisheries. Simply titled Plankton, it was boldly styled in all-caps mid-weight plankton-green slab serif on slime-rock-colored 80lb matte cover stock. What did Louella know about plankton that needed to be staple-bound and widely reproduced in a government report? Let’s find out.

“The word ‘plankton’ was derived from the Greek ‘planktos,’ which means ‘wandering.’ It is a collective term applied chiefly to all those small, extremely diverse forms of plants (phytoplankton) and animals (zooplankton) that drift aimlessly with the currents in all natural waters and in artificial impoundments. Most of the forms swim feebly and are incapable of making long horizontal journeys except as they are swept along by persistent winds and currents.” is how the first woman scientist of the US Fish and Wildlife Service (originally US Bureau of Fisheries) begins the pamphlet. A gentle but no-nonsense tone that drifts throughout the modest 13 page book.

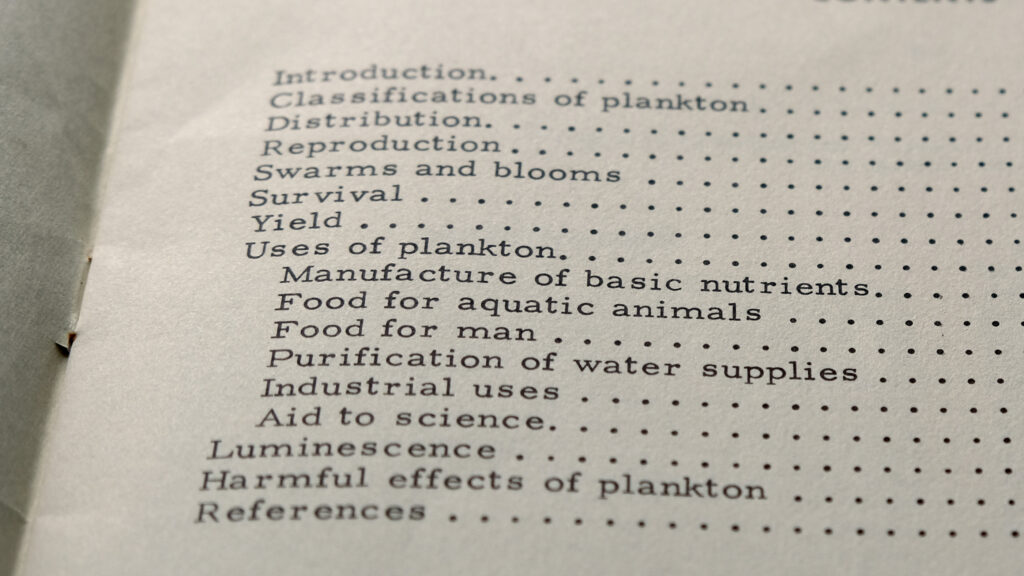

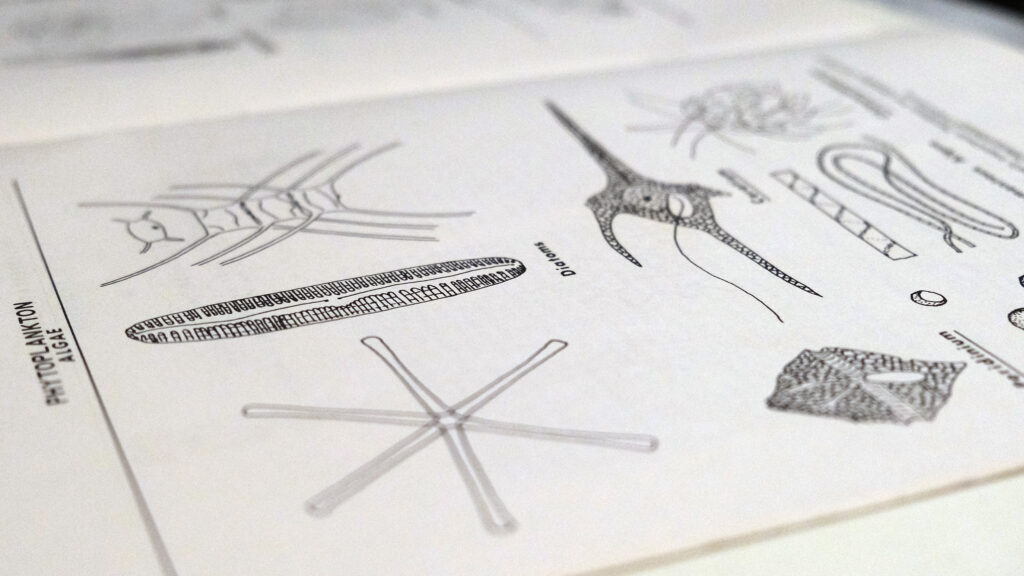

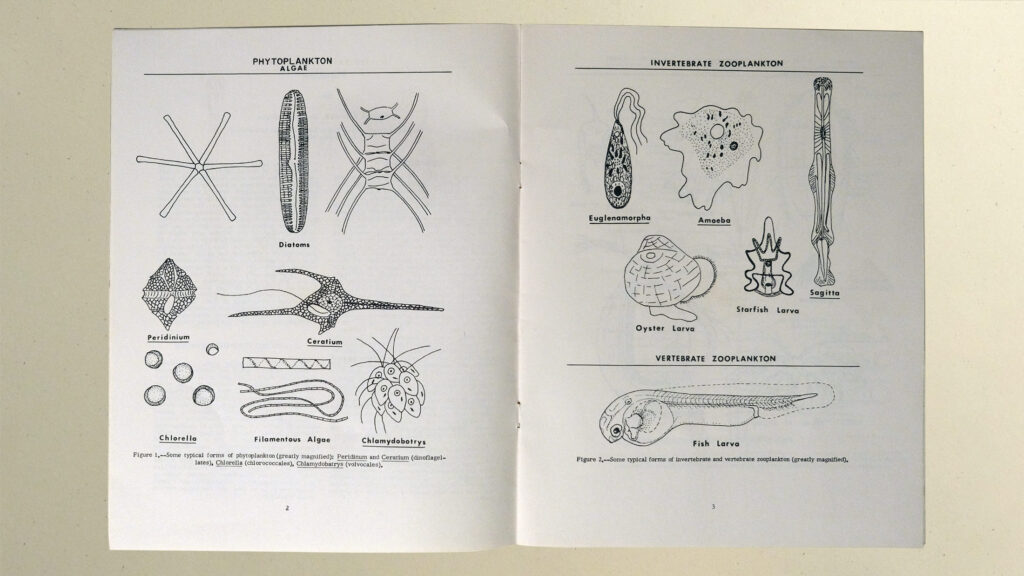

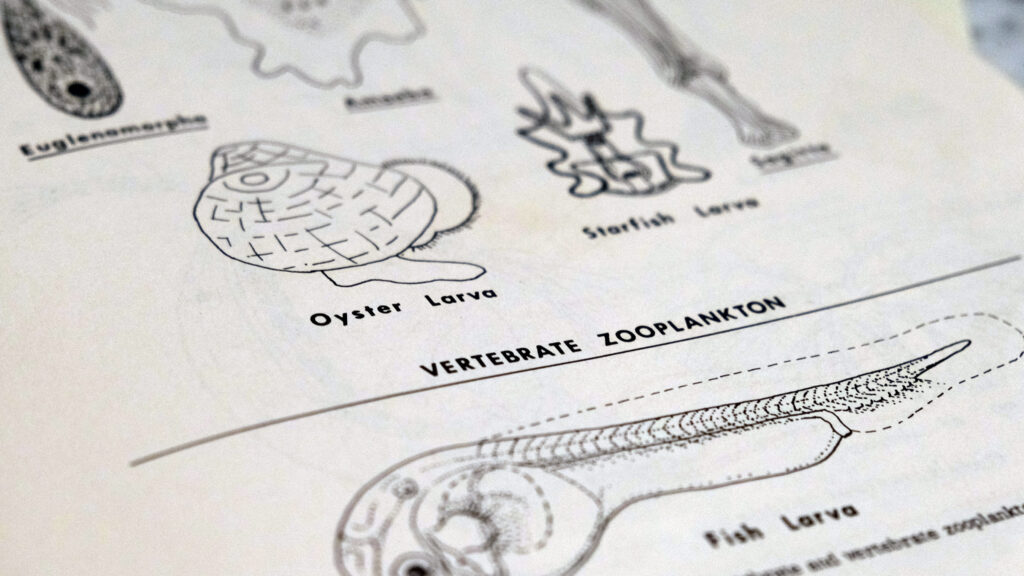

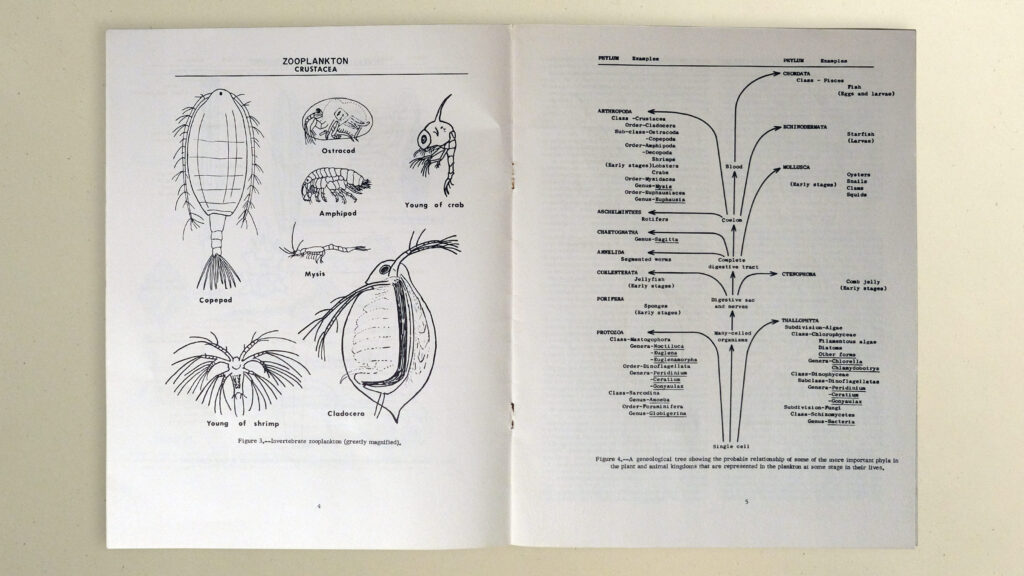

While most of the government plankton propaganda pamphlet consists of text espousing the scientific parameters and importance of these tiny creatures, it also contains plenty of beautiful illustrations of them. Dr. Cable was not just a pioneering American ichthyologist she was also an excellent scientific illustrator.

The drawings of oysters, starfish, and fish larvae are as transfixing as they are informative. They would look great on a tote bag. According to the main government fish website, Dr. Cable “spent her first year with the government sketching fish species at the federal biological laboratory at Beaufort, North Carolina.” She later illustrated a goby species that was eventually named after her: Cable’s Goby (Eleotrica cableae). We can all aspire to have a goby named after us.

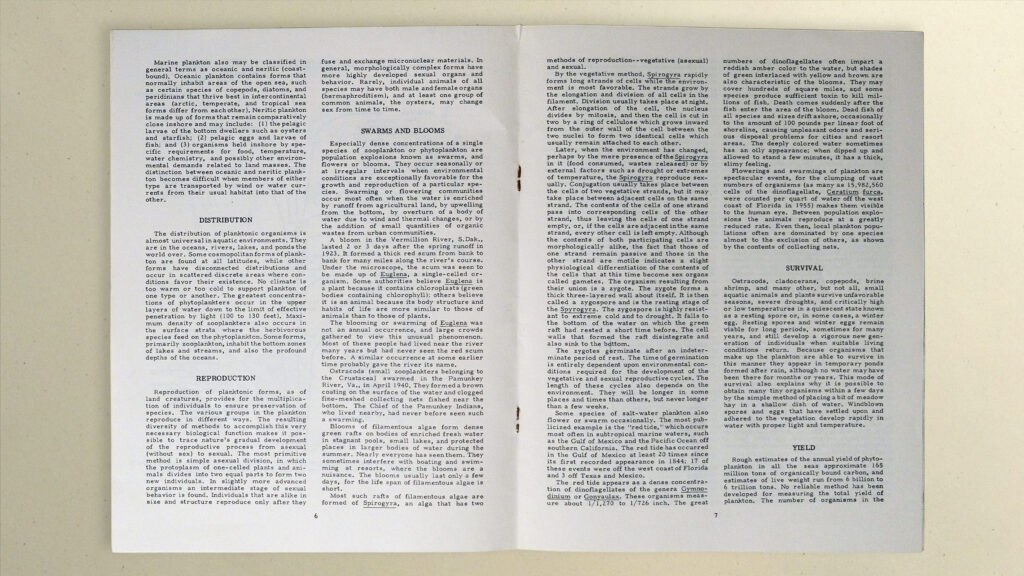

A bloom in the Vermillion River, South Dakota, lasted 2 or 3 days after the spring runoff in 1923. It formed a thick red scum from bank to bank for many miles along the river’s course. Under the microscope, the scum was seen to be made up of Euglena, a single-celled organism. Some authorities believe Euglena is a plant because it contains chloroplasts (green bodies containing chlorophyll); others believe it is an animal because its body structure and habits of life are more similar to those of animals than to those of plants.

Plankton by Louella E. Cable

Apparently, this publication is merely a revision of the original, titled “The Value of Plankton as a Food” (Fishery Market News, Nov. 1943, vol. 5, no. 11), also by Louella E. Cable While the original seems to be forever lost to the dark and unforgiving Mariana Trench of time, we managed to track down a reference to this mysterious and controversial piece of writing in something called the Marine Biology Laboratory Library, located in Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

Was the government afraid of plankton being used as food? Was Big Agriculture behind this title change? We have lots of questions.

A boat ride after dark at sea is pure delight when the bow wave and the wake behind the boat sparkle with tiny points of light known as luminescence.

LUMINESCENCE from Plankton by Louella E. Cable

“If the boat happens to be small, reach into the water; your hand will come out with some of the points of light clinging to it. Rub your hands gently together and feel small prickles. Put the bits of light into a drop of water under a microscope, and the wonderful world of dinoflagellates comes to life for you.”

There are unsanctioned and ungraceful reproductions of this pamphlet for sale on terrible, Earth-destroying websites, but we recommend tracking down an original on eBay or through rare book marketplaces to truly honor the plankton—and Louella E. Cable, the first woman government fish scientist and illustrator. Also, the paper and smell are just better.